Opinion: Asian cooking style works better for U.S. students

Julia English | Contributing Illustrator

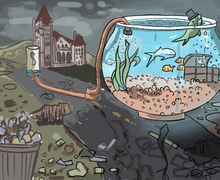

Asian meals offer a dorm-friendly alternative to processed, fried foods, our columnist says. Conscious meal preparation can prevent the long-term health consequences to more convenient choices.

Get the latest Syracuse news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

In kitchens of other countries, the way food is prepared is intentionally healthier than the way it’s done in the United States. Americans don’t consider enough how our cooking habits, not just eating, have a direct influence on our health. Asian cooking techniques, entrenched in simplicity and tradition, offer a refreshing perspective on welfare, sustainability and lifestyle.

The American diet’s prevalence of frying — a method that increases unnecessary calories and harmful compounds — has long-term consequences such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer.

The potential of vitamin-rich foods like tofu in American menus isn’t maximized. Preparations like tofu nuggets or fried tofu tacos smother the protein in refined oils and harmful coatings. Heavy sauces high in sugar, salt and saturated fats transform a low-fat, heart-friendly food into a calorie bomb that fuels obesity. What can often be a star ingredient becomes another victim of overprocessing in America.

Traditional Asian diets meanwhile avoid ultra-processed foods and use whole, minimally-processed ingredients. Fresh vegetables, rice and tofu are staples of many plates, and the cooking methods preserve nutritional value without relying heavily on fats or oils. Adopting these dietary principles can serve as a powerful countermeasure to the global health risks posed by the spread of American eating habits. This approach not only minimizes harmful additives, but also aligns with keeping your body free from preventable disease.

Picture in front of you a bowl of perfectly steamed rice with a medley of vibrant vegetables and a drizzle of soy sauce on top. It’s a simple everyday meal in many Asian households, yet it’s a far cry from the fried and processed foods dominating American college cafeterias. The traditional practice of cooking rice with pandan leaves or ginger not only enhances flavor but may also reduce harmful compounds like acrylamide, a carcinogen that forms during high-heat cooking.

Some types of Asian cooking also incorporate herbs and spices with remedial properties. The traditional Indian eating practices rooted in Ayurveda emphasize the concept of food as medicine, aligning meals with individual physical needs, seasons and environmental factors. Turmeric, a cornerstone spice of Indian cuisine, is revered for its curcumin content, exhibiting anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties and reducing the risk of chronic diseases. Similarly, ginger’s warming properties are particularly valued in Ayurveda, and such additions enhance flavor while contributing to long-term benefits.

My meals growing up in India often involved steaming idlis, light boiling lentils for dal or poaching fish in aromatic broths. Japanese dishes like miso soup incorporate silken tofu, while Korean cuisine utilizes tofu in hearty stews like sundubu-jjigae. These methods aren’t just about tradition — they’re about health. Steaming retains more vitamins and minerals than boiling or frying. A study published in the Journal of Food Science found that boiling broccoli depleted its vitamin C content and lost its flavor more than when steamed, similar to proteins like fish, chicken and tofu.

The dominance of American eating customs is reshaping food habits globally as heavy reliance on ultra-processed foods and animal products are often marketed as symbols of progress and modernity. In many developing nations, traditional plant-based diets have been replaced by fast food and processed items, driven by cultural perceptions tied to neocolonialism that equate American lifestyles to a higher social status. This shift comes at a cost. These foods, ranging from packaged snacks to ready-to-eat meals, are often calorie-dense but nutritionally poor, which emphasizes a saddening trend of people unnecessarily pushed further away from eating healthy.

Cole Ross | Digital Design Director

College cafeterias often represent a microcosm of the broader American dietary habits, dominated by processed foods and sugary beverages. These cafeterias, while convenient, reduce students to destructive eating patterns as they balance tight schedules and limited budgets.

For those juggling packed schedules, the notion of slowing down to cook meals might initially seem impractical. But, incorporating batch cooking or meal prepping actually saves time for students. Steaming a large portion of vegetables or boiling grains like rice or quinoa at the start of the week provides versatile bases for multiple meals, cutting down daily prep time.

Water-based cooking offers college students a way to stay nourished without relying too heavily on processed comfort foods. Simple dishes like soup, steamed dumplings or poached eggs over rice are quicker to prepare than you think, but also affordable — perfect for the Syracuse University schedule.

Learning from diverse traditions is important for young adults trying to figure out what works best for their well being. Incorporating even one or two water-based techniques can transform how what you eat affects your body.

Try replacing one fried meal this week with something steamed, boiled or poached. Explore dishes from various Asian cultures and experiment with flavors like soy, ginger or sesame oil. Cooking, much like college, is about exploration. These slight, intentional alterations aren’t just about eating differently — they’re about rethinking how food fuels your body and mind. A healthier, more mindful lifestyle starts with realizing what you’re already consuming and how it’s being prepared.

Sudiksha Khemka is a freshman nutrition major. Her column appears bi-weekly. She can be reached at skhemka@syr.edu.

Published on January 16, 2025 at 12:02 am